Mr BRAINWASH, a major Street Art artist and...

BOB TONIC

BOB TONIC is

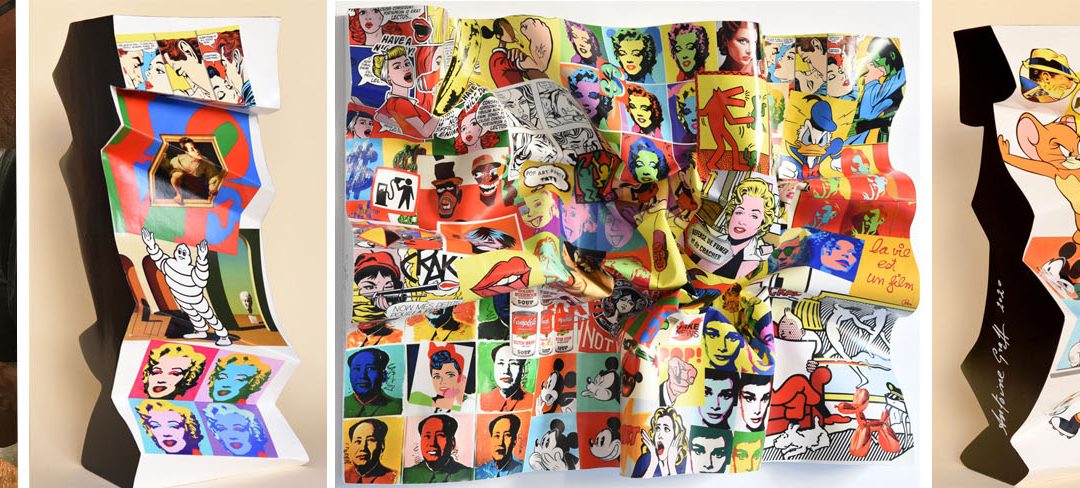

Bob Tonic offers sculptures in resin, bronze, concrete, one-of-a-kind or limited edition works. BT is a creative team created in New York City in 2018 by two former French advertisers, “because we were already working there, it’s a cradle of urban arts, with a tough audience that has seen it all…” Bob Tonic is an experiment: can we put impeccable technical means at the service of neo-pop works? Can we approach this market – with its dealers and galleries – like a start-up?

Self-interview Bob Tonic

Why take a pseudonym, Bob ?

“Because we are a duo, our initials are double B’s. Bob makes sense. Bob makes sense. We come from advertising, we spent our lives in a world of marketers, halfway between pure creation and hard business. Our deepest references are advertising and pop culture, an adoration for magazine covers and retro posters; so yes, the name Bob Tonic is a vintage collage, an ironic and retro facade, which allows us not to take ourselves seriously in a committed attitude, it’s anti-nombrilist; what we propose should be more interesting than “who we are”. Bob, first of all, is the same perfect symmetry as pop, so it is our vision, our proposal. Tonic, because we both have a great positive energy, we have often risen from the bad blows of life. There is this bitterness in the tonic which resembles the real life… And then it mixes well with gin, vodka; urban art is a giant cocktail where everything would be ideally well dosed. We mix, we cut, we put back together pieces that touch us. We worked a lot on the basic idea before starting at the end of 2018.

And what is the idea exactly ?

“Urban art is the antithesis of our former profession. It’s “No Display”. All this weed that grew in the 60s, counter-culture, protest, explosion of the big consumption. It was totally on the fringe, and of the art market, and of legality. It’s funny to see how today, in the 2020s, that margin has become the norm. And the weed has become this vast, well-cultivated field.

MAZEL & JALIX

Form and substance come together and the use of bronze, in its most primitive way, stressed the subject of Mazel & Jalix, staging the simplest aspects of life.

On boxes, pedestals, plates, the fruits stand but never freeze, so many vanities placed in the garden of Hesperides where fruit at the center waits to be selected and tasted, not as an object of conflict but of pleasure, then the bronze becomes a living object of desire. However, the careful observer will see that, here and there, withering already appear and the fruit, too ripe, stains and bends under its own weight. Decomposition is already there, leaving its stamp on Mazel & Jalix’s work. Create brings the work to its end, its decay, but subsequently the fruit returns to the earth in an eternal renewal.

Such as 18th century’s Naturalists, Mazel & Jalix build a ‘natural’ collection between the research and idealization. Sculptures’ titles reduce works to studies. It is to gather and name a chosen specimens set, emblems of a changing nature.

Interview :

Why did you choose sculpture ?

Jalix: Graduate in horticulture, sculpture allows me to reveal that fascinating plant world and the choice of bronze was imposed on me by its sensuality. I like playing with the disproportion and highlight little details, those that no one sees but which take an extraordinary dimension for me.

Mazel: we wanted to be able to touch, with the tip of our finger, life in all its banality and sensuality: what I mean to say is that painting wasn’t enough and we needed to move onto working in three dimensions as a way to highlight my subjects.

You create your own extraordinary garden, it seems that you have some Gulliver in you.

Jalix: Once again, it all depends on your point of view, is the fruit enormous or ridiculously small?

What I am sure of is that in each sculpture exists life.We are gardeners amazed by their own crop. The subject we focus on leans to the extreme. We like the idea that creation chooses its own limits and escapes from rules of proportion and of the ideal form that we impose to it. It takes its own space.

Mazel: I believe that as we’ve already said, the subject itself brings us back to the idea of simplicity.

Jalix: At the same time, sculpture is also a complex process of creation process, the casting, the engraving, and the patina.The difficulty of the work should never appeared. Its simplicity is the result of a long creative evolution like the mystery of life.

GRAFF

ANTOINE GRAFF

Antoine Graff’s destiny was not “folded” from the start. Of course, born a painter’s son and grandson of a blacksmith, it was inevitable that the arts would have an effect on him. Not to mention he has a surname which sounds like a pseudonym! Yet his career panned out a bit differently, between colouring, adventuring, and paper folding.

Antoine Graff started to paint at the age of 8. At 14, the age when adolescents typically begin their teenage crises, he received his first commission! In 1954, he left his native Alsace and started studying fine arts in Paris, but primarily cut classes. His instinct encouraged him to visit the studios of artists Zadkine and Lhote. Zadkine, a sculptor, liked the feet of Graff’s statues. The painter Lhote considered him to be an excellent illustrator, once he abandoned Delacroix! Graff was trained by these two masters, and good ones at that! Surely an umpteenth tomfoolery.

His real adolescent crisis came at the age of 26, as he thought he was no longer “skilled.” It was a period of emptiness, when the homo habilis engaged in a fiery war against himself. Yet the biggest paradox is that this time allowed him to produce his work, supported by these his two gallery owners art dealers. However, nothing came of it.

He created a prestigious business of window displays for pharmacies that would make any seasoned businessman envious. The patent that he filed brought him 11 thousand pharmacy clients on a plate! But the homo habilis was not content with window displays. Instead, Graff took up print advertising. His expertise soon attracted artists. Télémaque, Arman, César, and Villeglé all lined up in his new back room to have their original prints produced. His business gradually evolved from printing to art publishing. He acknowledged it not nostalgically, but with an assertively humorous sense of perspective. His wealth grew, he travelled, and money was easy. Then came the ultimate stroke of genius: he was given the luxury of creating the gallery La Main Blue in Strasbourg, where he held exhibitions for Alechinsky, Bram van Velde and even Télémaque. For five years, he had his ideal project; tinkering in art.